The behaviour of the islands fauna despite human presence is also so special. Being largely a marine environment, the boobies nest their young in any open place they find. All of the significantly sized indigeous land animals seem to be vegetarian (iguanas and tortoises) so the boobies have no predators. It also highlights what easy prey boobie chicks are for introduced species such as rats, cats and foxes. The only creatures that displayed any sort of reticence to human presence were the small ghost crabs, which ran for their burrows at the slightest hint of movement.

In addition to the photos taken of the islands birds and reptiles, I also did some snorkelling and saw manta rays, and quite an array of tropical fish. I also had the privilege of swiming with sea lions.

The work done by the Charles Darwin Foundation in conjunction with the Galapagos Islands National Park (97% of the islands are national park, plus there is a 20 nautical mile marine park around the islands) to restore the islands is ongoing. Their biggest project (and biggest success) was the eradication of feral goats and pigs from Isabela, the largest island in the archipelago. This project took more than 10 years, and the local plants and animals sprung back to prominence almost as soon as the goats were cleared. They also have had great success with the various tortoise populations through captive breeding. One species population has grown from thirteen turtles (11 female and one male taken from the wild, plus 'Diego', a male tortoise who was previously residing at the San Diego Zoo in California) to more than 1,200 tortoises now living in the wild.

So should everyone come and see the Galapagos Islands? It is a tricky question. There were 145,000 visitors last year (versus a stated target of 120,000) and cruise ship numbers and island visits are capped. I don't know where the line can be drawn between trying to undo past human interference and continuing to allow visitors to the islands with their cameras, and clumsy feet and risk of introduction of further invasive new species. The Galapagos is an expensive place to come, the tourist boat operators pay for island visitation rights, and every tourist is required to pay a US$100 park entry fee on arrival, most of which goes to the maintenance of the national park. So despite being a vacation spot for the rich, at least the tourists are contributing (if only financially) to the solution.

I've cut the 400 or so photos I took in the Galapagos down to the 30-odd shown below. If you click on any photo, you get the full resolution image, in case anyone considers my humble photography worthy of using as a screensaver, forwarding or printing.

A pair of mating green turtles. This is breeding season and the females are making nightly pilgrimages up the sand dunes of Galapagos beaches to bury their eggs. Each female will make around two or three visits to the beach to lay, with the eggs hathing four months later.

A flamingo feeding in a lagon on Baltra. After a drought in the mid 1980's the population of flamingos declined significantly, and there are now about 300 in the Galapagos.

A marine iguana out for a walk on the beach.

Thousands of crabs swarm all over the rocks surrpounding the islands. Like most of the other creatures, these are only found in the Galapagos arhipelago.

A blue footed boobie, resting on a rock ledge.

Masked Boobies nest on the ground (as do blue footed boobies). As there are no natural predators, there nests are built wherever there is open space.

A masked boobie caring for its egg. Both parents look after the egg, with one minding the hatchling while the other goes out to feed.

A masked boobie with a newborn hatchling, probably no more than 24 hours old. Despite its fragile new offspring, it showed no concern at (or even interest in) people walking barely a metre away.

For the first month, one parent will stay with the hatchling at all times however, as they grow, both parents will go out to fish and the chicks wait patiently (and hungrily) for their return.

A red footed boobie chick being sheltered by a parent.

Another red footed boobie and chick.

Fur seals were about the only animals to acknowledge human presence. This one was he was asleep on the path in front of us and expressed his annoyance verbally at having to move before diving into the water.

A nesting spot on Isla Genovesa. If you click on the image, you get a larger version. An almost impossibly beautiful location.

A male frigate bird strutting his stuff. The red protrusion from his neck (which inflates like a baloon) is there to impress the lady frigate birds.

A frigate bird takes flight.

Red footed boobie. Just visible in the photo between the green leaves are the bright red feet.

A baby sea lion feeding from its mother. Like most Galapagos creatures, both were indifferent to my presence even though I was only two metres away.

A pair of boobies. I believe the instruction from the one on the left is not to fly too close.

Sunrise at Isla Bartolome.

A pair of Galapagos penguins, which are endemic to the islands and are also the only penguins found north of the Equator. They live in the lava tubes formed when lava reaches the sea.

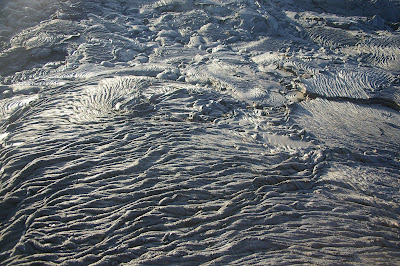

Lava flows on Isla Santiago. There are 36 square kilometres in this lava flow. The hot spot that forms these vocanic islands remains stationary while the Cocos Plate (one of the earth's ocean plates) is moving west. The only current active volcanoes in the Galapagos are on Isabela and Fernandina, the two westernmost islands.

Detail of cracked lava showing the mineral composition, visible as a rainbow of colours. It is these minerals that give some of the beaches distinctive red or black hues.

View of Isla Bartholome featuring 'The Pinacle' rock formation on the right with Isla Santiago in the background. The boat visible at far right is Spondylus, which I stayed aboard during my Galapagos visit.

A colapsed volcano caldera. Only the ring and centre remain, with the rest washed and blown away. If the images above and below look familiar, Bartolome was one of the settings for the movie Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World.

Female green sea turtle having a rest. The beach is currently littered with sea turtle nests as the females climb up at night and deposit 100-120 eggs before burying them and returning to the sea.

White tip reef shark. There were about half a dozen milling around the beach when I took this photo.

The beach on Bartholome.

A resident lava lizard, curious as to why an Australian with a camera seems so interested in him.

Another sea turtle coming in for a rest on the beach. Out of shot, a couple of male sea turtles are waiting for her to return to the water.

A pair of sea lions arriving on the beach. The red colour of the sand comes from volcanic minerals from when the island was formed.

Frigate bird in flight.

Squardon of frigate birds. These were easy to photograph as they were gliding along in the updraft reated by the boat for about five hours.

The large tortoise in the centre of the screen is known as Lonesome George, who lives at the Charles Darwin Foundation research facility on Santa Cruz. Unfortunately for George, when he was rescued several decades ago on Pinta, he was the only tortoise they could find and therefore appears to be the last of his species. The other two tortoises are females from Marchena, the nearest island to Pinta and the closest genetically to George. The researchers hoped might be able to successfully mate with George but have had no success to date.

A land iguana. These were previously the subject of a breeding initiative by the Charles Darwin foundation, however it has been so successful that the animals now breed happily in the wild.

Another resident tortoise at the Charles Darwin Foundation. The shape of the shell around the neck of the tortoise indicates how far up it has to stretch to reach its food supply. Most of the resident adult tortoises used to be pets for Galapagos Islands residents, so cannot be released back into the wild. As they live to be 150 to 200 years old, no one is exactly sure of they're actual ages (and the tortoises themselves aren't telling).

My favourite native of the Galapagos Islands, would have to be the marine iguana, a creature not only incredibly well adapted to the local environment, but also incredibly improbable in its own right.

Like all reptiles, marine iguanas are cold blooded and start the day with a dose of sun on the black volcanic rocks which they live to get their metabolism moving. They then

plunge into the water in search of the algae that they feed off. On the rocks close to shore, where the whole population has access, the algae has been reduced to a thin green layer, which the females and juveniles lick to get nutrients. The fully grown males swim out into the ocean to go in search of the fully grown algae (seaweed) which is where the challenges really start.

plunge into the water in search of the algae that they feed off. On the rocks close to shore, where the whole population has access, the algae has been reduced to a thin green layer, which the females and juveniles lick to get nutrients. The fully grown males swim out into the ocean to go in search of the fully grown algae (seaweed) which is where the challenges really start.The marine iguana can hold its breath for up to an hour and swim down to quite respectable depths, however seldom stays under water for more than 15 minutes, as the cold ocean water causes their body temperature to start reducing. If they don't (or can't) keep their temperature up, they suffer hypothermia and pass into a sort of coma, then drift on the ocean alive, but unable to move until they either wash up on land or die.

The marine iguana has developed an organ behind their eyes (similar to penguins) which extracts the salt from seawater so they can metabolise the water. This works more efficiently in these creatures than any other on the planet, and allows them to metabolise water twice as salty as that which they actually drink in the ocean.

The photo to the right has a swimming marine iguana centre of picture, oblivious to the snorkelling tourists and boats around him.

The photo to the right has a swimming marine iguana centre of picture, oblivious to the snorkelling tourists and boats around him.Marine iguanas are only found in the Galapagos Islands, and are also the only ocean dwelling reptile on the planet. They live on fresh lava flows, that otherwise support almost no life, and thrive to such an extent that there are hundreds of thousands living in the Galapagos.

No comments:

Post a Comment